Brew With Us ESSENTIALS – managing yeast flavour

Great fermentations

All these descriptions of yeast flavours sound great – but yeast has a life of its own!

Getting your yeast to behave is an important skill…

Yeast wants to ferment: give it some sugar and away it goes. But yeast isn’t a machine, and getting it to give you the results you expected can require some effort.

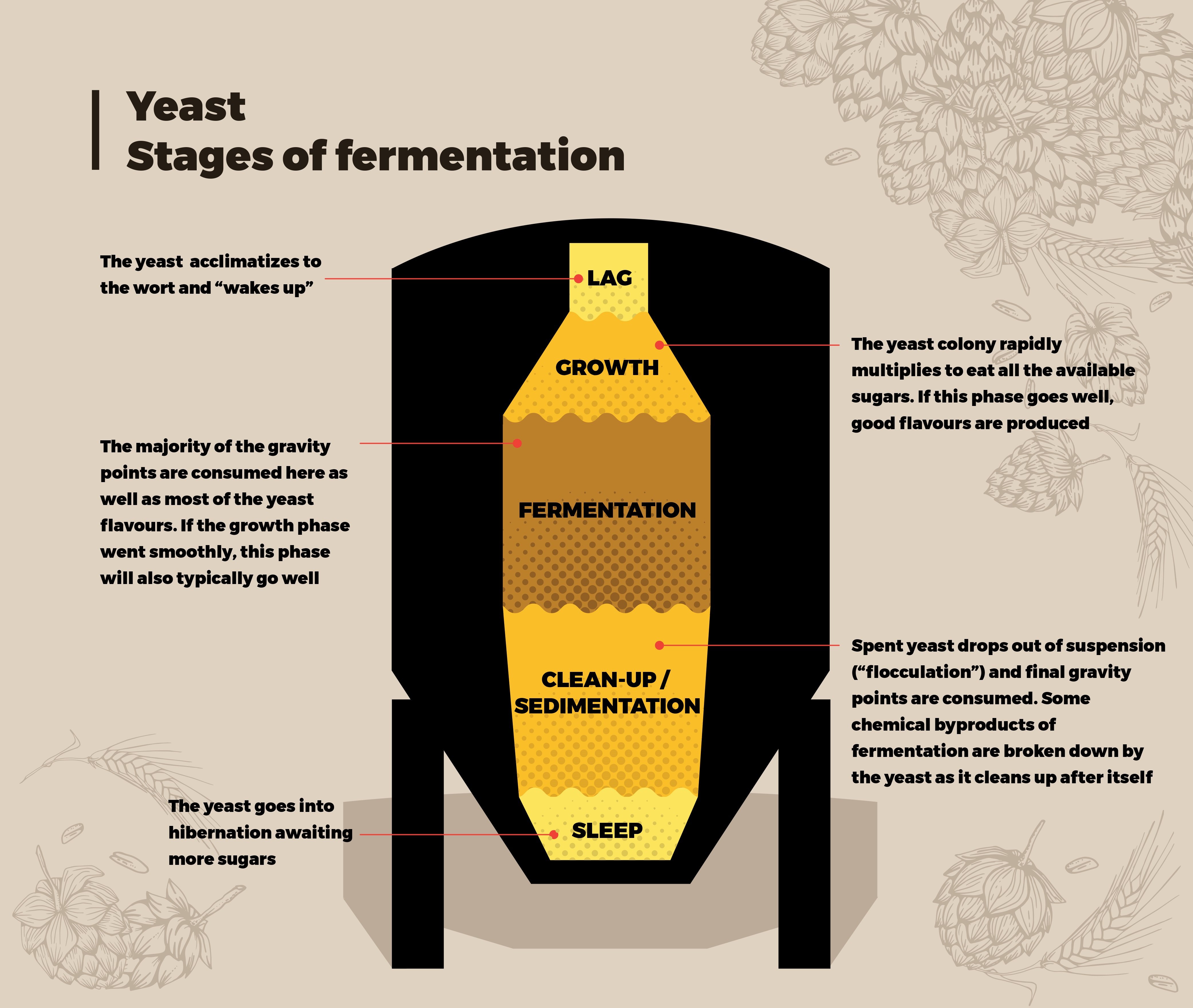

Let’s remind ourselves of the stages we see in fermentation:

Lag → Growth → Clean up → Sleep

Lag is the time between adding (pitching) the yeast and fermentation beginning. During the growth phase, the gravity of the wort drops, then in the clean up phase the gravity stabilises and leftover chemical compounds are broken down. Lastly, the yeast goes into hibernation and drops down to the yeast cake at the bottom of the fermenter.

Nutrients

Yeast loves sugar, but we all need vitamins and minerals. You can buy special yeast nutrients, which are blends of trace minerals and other compounds that help yeast grow well. These aren’t essential – you can ferment brilliantly without them – but they can be helpful when working with high gravity worts, colder temperatures, or less fresh liquid yeasts.

Normally, nutrients are added for the last few minutes of the boil. This helps them dissolve and mix evenly through the wort. Some nutrients are used differently so check the instructions.

Pitching rate

The pitching rate is how much yeast you add at the start of fermentation. Using too little yeast for the size and strength of your batch is called underpitching, while using too much is called overpitching.

Underpitching is a common cause of fermentation issues. While yeast will grow to fit the level of sugars available, if the yeast colony is too small or weak, you might see a longer lag phase – meaning the wort is vulnerable to infection for longer – and the growth phase might struggle to get going. This might mean in turn that the yeast gives up earlier than expected and you don’t reach your expected final gravity.

Another potential impact is on the flavour. If the yeast is stressed from trying to grow from a weak colony, it may produce off-flavours.

Overpitching is less common – you would need to throw four or five times as much yeast in as normal to hit this – but it can also cause some problems. If there is too much yeast for the sugar around it, then it won’t grow as much as it should – leading to a lack of flavour – and it might get lazy and not finish up fermentation properly, leaving off-flavours behind.

Working out the correct pitch rate can be difficult to calculate without special tools. Handily, though, the number of cells in a packet of dried yeast is pretty much perfect for a 20-23L batch expected to finish around 4-5% ABV: around 10 million cells per ml of wort.

Higher gravity beers begin with more sugar, so they need more yeast. Recipes for high gravity beers will often suggest using two packets of yeast. Another situation where you might need more yeast is when you’re fermenting at low temperatures, such as when you make a lager. Yeast grows faster at higher temperatures, and more slowly when it’s cold. We know that lager yeasts are specially adapted so they still grow in the cold, but they still go relatively slowly. It can be a good idea to increase your pitching rate to shorten the lag phase and protect your beer against infection.

Pitching temperature

Yeast grows faster in the warm – so we should always pitch at a warm temperature, right? Not necessarily! Too warm and the flavours produced in the growth phase can be harsh and unrefined. But too cold and the yeast will go slow and produce less flavour overall.

Most yeast labs provide the ideal temperature range for each strain. This gives you a range where the yeast will grow well and will also produce good flavour. Some brewers like to pitch towards the lower end of the ideal range: fermentation generates heat, so as the yeast gets going the beer will warm into the higher part of the ideal range by itself.

It’s a good idea to make sure your yeast itself is at the same target pitching temperature as the wort you’re adding it to. This avoids heat shock: a big difference in temperature can harm the yeast colony and may produce bad flavours. For typical ale pitching temperatures, take the yeast out of the fridge a few hours before your brew to let it warm up slowly.

Stuck in a rut

Sometimes fermentation can stop or stall at a higher gravity than expected. If you are within one or two points of the expected FG (e.g. 1.016 compared to an expected FG of 1.014) this is probably okay, but if you’re a long way off (e.g 1.030) you may have a stuck fermentation.

There are many causes for a stuck fermentation, including underpitching and heat shock, but whatever the reason, the yeast has run out of energy to break down more complex sugars. Yeast is lazy and always goes for simple, easy to digest sugars first, and leaves more complex stuff for last. But yeast also gets full up. With a stuck fermentation, this has happened sooner than we expected.

Your job with a stuck fermentation is to get the yeast going again. The first thing to try is to raise the temperature a little – warmer temperatures encourage yeast to grow. Give it a couple of days, then if you still don’t see any signs of life, add a little yeast nutrient to make sure the yeast has all the vitamins and minerals it needs. Again, give it a few days.

If you’re still stuck, you are best off pitching more yeast. The ideal way to add more yeast is to make a yeast starter from the same strain, then pitch this in when the starter is at high krausen. The yeast will be really active at this point and ready to get to work. If a starter isn’t possible, the next best choice is a neutral and high-attenuating dry yeast, such as the Nottingham strain.

If none of this helps, the problem may stem from your mash – you might simply have a less fermentable wort than expected.

Diacetyl rests

It is often a good idea to raise the temperature of your wort towards the end of the growth phase, when the gravity is beginning to stabilise. This is called a diacetyl rest. Higher temperatures encourage the yeast to not give up and munch through the last few gravity points. The warmth also helps reduce diacetyl levels – this is a common flavour produced in the growth phase that is often said to taste a bit like butterscotch, or if you’re from the USA, creamed corn.

A small amount of diacetyl is acceptable in traditional British ales, but is considered a flaw in pretty much all other styles. The diacetyl rest should be at around 18-20°C for both lagers and ales.

Cold crashing

We know from our hop section that if you dry hop your beer, it can be a good idea to drop the temperature of the wort down to 3-4°C before transferring out of the fermenter – this is called a cold crash. This step helps pull the dry hop sediment out of suspension so you transfer clearer beer. Cold crashing also helps pull out clumps of yeast that might be floating around, so it’s a good idea even when you’re not using dry hops.

The British fungus

Sacc finishes fermenting in days and kveiks can be done in hours.

How about a yeast that finishes in… years? It’s time to get say hello to Brett!

And we’ll learn why some brewers deliberately infect their beer with bacteria – and why you might want to follow suit…