Brew With Us ESSENTIALS – Brett and bacteria

Let’s get funky

What makes wild ales “wild” and what makes a sour, sour?

It’s fermentation, Jim, but not as we know it…

So far we’ve focused almost exclusively on a single species of yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Sacc for short), and some of its close relatives. This time we’re introducing a completely new yeast, which ferments very differently: Brettanomyces.

The name means “the British fungus”, and Brett (as we’ll call it for short) and the flavours it can produce were called “English character” in the 1800s. Most likely this stems from Brett living in barrels where beers were stored and aged: over time, Brett would break down and ferment sugars and proteins left over from a normal Sacc fermentation and add its own flavours. Where Sacc usually completes fermentation in a few weeks, Brett doesn’t typically even begin until after then, and can take months or even years to develop its character.

This ability to consume sugars that Sacc can’t is one of the reasons Brett can be seen as a spoilage agent in winemaking and in “clean” breweries. It’s understandable: you get your beer fermented to the right degree, with the right balance of residual sugar and flavour, then after a few months, the beer has turned very dry, is overcarbonated, is stronger in alcohol, and tastes completely different – eek!

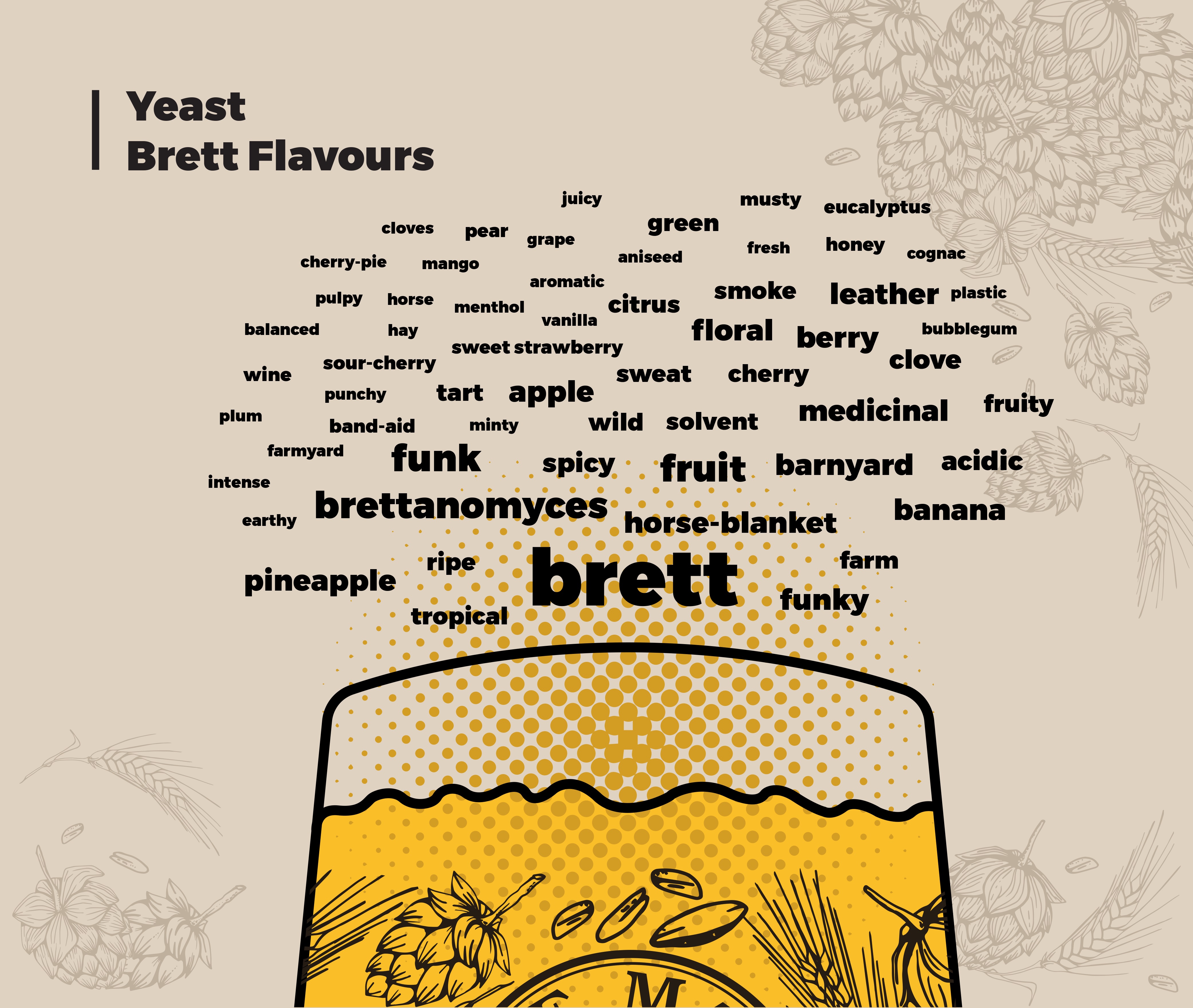

The range of flavours Brett can produce is very wide, but some common descriptions include:

Brett can also produce acetic acid (vinegar) under some conditions, typically when there’s too much oxygen available. Add to this that Brett is very hardy, able to survive high concentrations of alcohol and very acidic conditions (as low as 2 pH), and you can see why Brett is considered a major enemy by many brewers!

Despite this, Brett has a lot of fans. The variety of its flavours and its long development time can make beers that are complex and take well to ageing. While some of the flavour components described above might not sound appealing, in the right balance they can become very delicious indeed.

Styles like lambic from Belgium are a showcase for Brett, along with other microorganisms we’ll meet a little later. These beers use a complex mash schedule called a turbid mash. This is deliberately not very fermentable for everyday Sacc, meaning there’s lots leftover for the Brett to get stuck into. Aged for years or even decades at a time, lambics are amongst the most prized beers around, in large part thanks to Brett!

There are several species of Brett, which behave quite differently. The two most commonly available to brewers are B. claussenii and B. bruxellensis.

B. claussenii is the species thought to be responsible for that historical “English character”, and adds notes of fortified wine, overripe pineapple, and leather. Like most Bretts, it’s not very strong in primary fermentation so it is better used in secondary fermentation such as barrel or bottle-ageing. It can take several months to show its hand so be patient.

B. bruxellensis is the variety used in lambics and many modern “wild ales”. This species is also better used in secondary fermentation, where it can add bright fruit, floral, and barnyard flavours in varying degrees. You will sometimes see mention of “Brett Lambicus” as a species – this is a family of bruxellensis strains that most closely resemble historical lambic strains. Some of these “Lambicus” strains can manage primary fermentation, so if you see a “Brett IPA” or similar, it’s likely been made with one of these.

There are dozens of Brett strains and blends available, many of which change seasonally or are available from smaller yeast labs. Explore!

Intentional infection

Bacteria are a bad thing in brewing – right? Well, in some styles, they’re essential! Lactobacillus and Pediococcus are bacteria that produce lactic acid, which is the main acid in sour beers like gose, berliner weisse, and lambic. Brewers will intentionally infect their beers with these bacteria – but strict cleaning is required to make sure unwelcome bacteria doesn’t come along for the ride. Neither Lacto or Pedio are particularly hardy, so just like with Sacc yeasts, they prefer a clean “blank slate” to work in.

There are challenges to working with these bacteria. Lactobacillus is killed by most hops, with most strains unable to tolerate more than 10 IBU. Pediococcus is fine with hops but can take a long time to produce sourness, and can also produce a viscous, ropey film as it grows. This “sickness” dissipates after time and adds a good flavour in the long term, but this process can take months.

For quicker souring without these complications, yeast labs have developed new strains that are easier to use. Lachancea thermotolerans is a species of yeast that doesn’t mind hops, ferments with similar flavours and speed as a clean Sacc strain, and also produces lactic acid along the way. This species is available commercially as Lallemand “Philly Sour”, The Yeast Bay “Berkeley Hills Sour Blend”, and Escarpment “Lactic Magic”.

Grow your own

Traditional lambic beers use “spontaneous fermentation”: they are left open to the air to allow naturally occurring yeast and bacteria settle on the wort and begin fermentation. In practice, it’s thought that a good amount of the yeasts and bacteria found in lambic come from the wooden barrels used as fermenters, with the same strains surviving between batches. Saying that, it really is possible to capture yeast from the wild. With some fairly simple equipment, you can capture wild yeast from your own garden, or from flowers, or fruit skins, or anywhere else you can think of! (be sensible and careful: not all wild yeasts may be suitable for beer or human consumption in general.)

If you’re feeling intrepid, check out Bootleg Biology’s guide to wrangling your own yeast.

Beyond barley. Beyond beer. Beyond your wildest imagination.

Yeast can ferment anything! Well, almost anything.

From cider to sake, let’s see how far yeast can go!