Brew With Us ESSENTIALS – introduction to malts

Welcome to the first step of your Brew With Us ESSENTIALS journey!

In this first section we’re focusing on the backbone of beer: malt.

Over the coming chapters you’ll learn about the different types of malts, sugars, and other grains we can add to beer.

When we talk about “malt”, we mostly mean “malted barley”. Raw grains of barley are squishy and starchy, like flower buds. The malting process dries each grain and turns starch into sugar, which allows you to get those sugars out to make beer.

Malting is a traditional process dating back thousands of years, though the technology has developed quite a bit since then. Maltsters take the raw grain from a farmer and transform it into the dry, uncrushed malt we see more often.

The first step of malting is to dry the grain. This is traditionally done over a wide, flat floor where the grain can be spread into an even, shallow layer. Once the grain has dried out, the maltster adds water to make it wet again! The grain reacts to the change in moisture and begins to sprout (germinate). Grain is a seed that wants to turn into a new plant, so as each grain germinates, enzymes inside begin unlocking those starches into sugar to help the plant grow.

Once the grain has reached the right level of germination, the maltster dries it out again to halt the process. This stops the sugars that were unlocked from being used up. The grain at this stage will still taste very “green” and vegetable-like, so the next stage is to toast lightly in a kiln. Depending on the type of malt being made, the grain can be kilned further for darker colours, or even roasted to turn it black. We’ll explore the many kinds of highly kilned and roasted malts in a later chapter.

The colour of magic

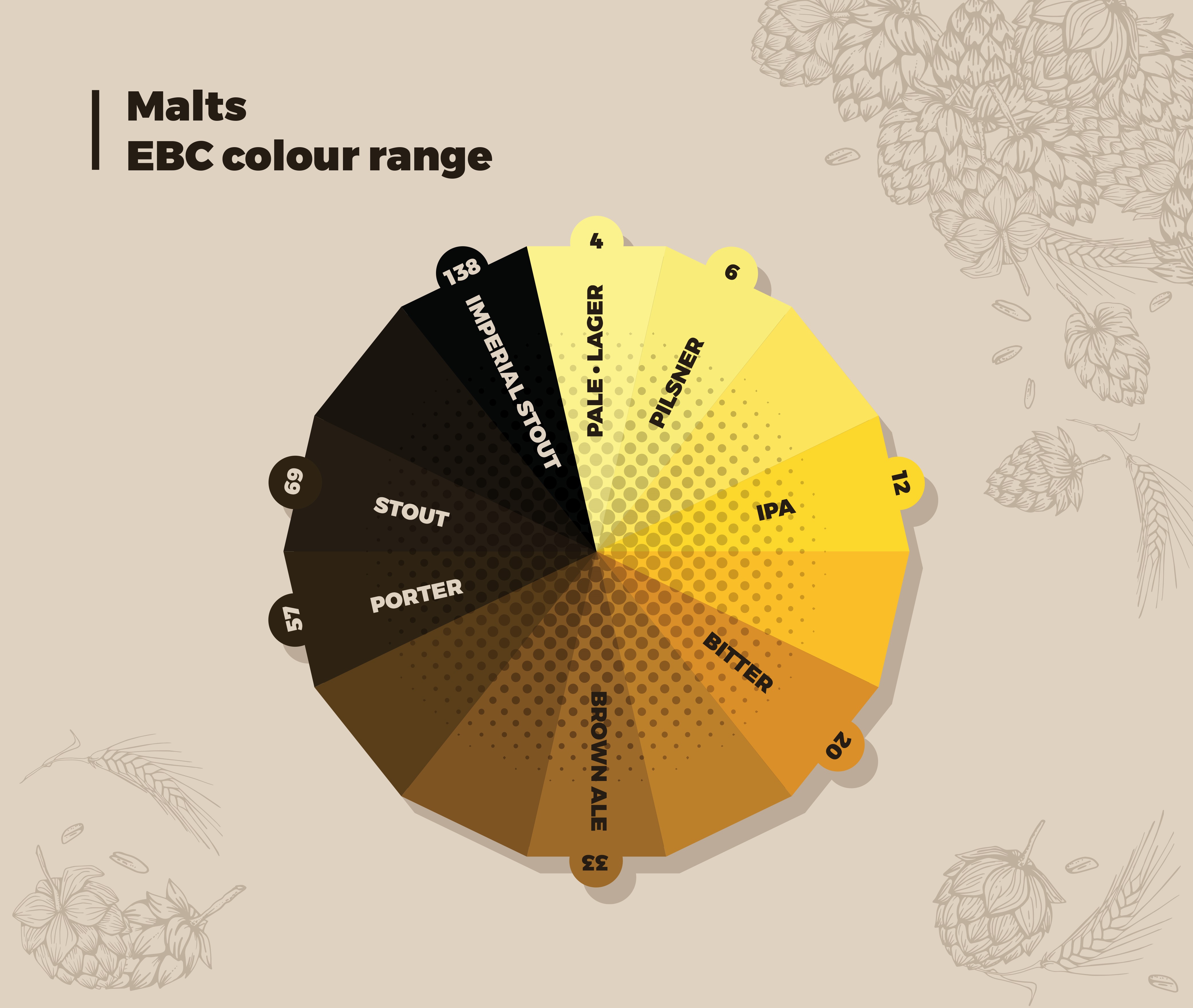

Malt can range from super pale straw colours all the way to deep black. We measure the colour of malt by EBC number (“European Brewing Convention”), with higher numbers indicating a darker colour. A pilsner malt will clock in at around 3 EBC – and a pilsner beer about the same – while the dark malts used in stouts can exceed 1000 EBC! As we’ll see, you mix both pale and dark malts to make a stout so the final beers are typically around 50-100 EBC.

EBC was developed as an alternative to two other colour scales that are still used elsewhere: SRM (“Standard Reference Method”) and Lovibond. Technically, Lovibond refers to the colour of malt, and SRM to the colour of beer. EBC can be used for both so we prefer this measurement.

All sorts of grains can be malted – wheat, oats, rye, etc. – but barley is most commonly used for brewing because it contains enzymes leftover from germination, the same ones that break starches down into sugars. When we make a mash from barley, those enzymes convert any remaining starches and more complex sugars into simple sugars that yeast can digest. Barley has far more of these diastatic enzymes than other grains, so even in beers based around grains like wheat, you’ll find barley malt is included to help unlock the sugars.

Milling

Before we can use our malt, we have to mill it. This breaks open the husk of the grain and exposes the sugary kernel inside – otherwise when we mash most of the sugars will stay inside the grain. The husk doesn’t contain sugars, but it’s still useful: it forms a natural filter to allow the mash to drain off. Without the husks, our mash would turn into a solid lump like porridge – the dreaded stuck mash!

Milling is very important and can be the difference between a good and a great beer. The smaller you crush the malt (a “finer” crush level), the more the husks are broken up, increasing the risk of a stuck mash. On the other hand, a coarser level of crush might not release enough sugars, leaving you with a weak, thin, and grainy-tasting wort.

The sweet spot is an even level of crushing, with the inner kernel fully exposed but enough of the husk still intact to stop the mash glueing up. In your hand you will be able to see coarse husks, fine kernels, and a small amount of floury husk. Especially fine crush levels will break up the husks more and release more flour, which can be a good idea for brewing methods like Brew In A Bag (BIAB) where there is a lot more water in the mash. However, the grain should never be completely pulverised into flour – too much husk can add an astringent grainy flavour.

Getting the crush level right is complicated by the fact that different malts – and even different harvests of the same variety – can have different sized grains. Unfortunately, you can’t just set a single mill gap and throw everything through! A malt like Golden Promise or Maris Otter has much bigger, plumper kernels, whereas dark roasted malts can be much smaller. Some other grains, like rye malt, would fall straight through a mill set up for Maris Otter without touching the rollers! We constantly calibrate and adjust our equipment to get the right level of crush from each grain we mill.

Once malt has been milled, it begins to dry out and lose flavour. This happens much more quickly when exposed to the air, so for best results crushed malt should be as fresh as you can – used within a few weeks or ideally less. We crush all our malts individually to order so they’re as fresh as possible. Keep crushed malts in the bags they arrive in until you’re ready to use them to seal in as much of the original flavour as you can.

Nice to malt you, to malt you… nice!

Next time we’ll look at the malts you’ll use more than any others: base malts.

From Maris Otter to pilsner, Munich to Vienna, we’ll cover the differences and key details you need to select the right malts for your beer.