Brew With Us ESSENTIALS – base malts

All about that base (malt)

In the last chapter we learned how malt is made and how to prepare it for brewing.

Now we’ll look at the malts you’ll use most often: base malts.

Base malts are malts that have enough enzymes left over from the malting process – enough diastatic power – to allow them to convert starches and sugars during the mash. Specialty malts or darker roasted malts often don’t have much diastatic power, so the sugars in them won’t be extracted into the mash by themselves. Base malts have enough power to convert both their own grains and others in the mash. Because of this, you’ll find base malts make up the vast proportion of any recipe you encounter – usually 75% or more of the total grist. You can even make beers from just a single base malt. Fortunately, base malts also tend to cost less than specialty malts!

Maris Otter and other ale malts

Because they make up such a high proportion of your recipe, choosing the right base malt is very important. Some specific varieties of barley are so prized for their flavour that they’re referred to by name. Maris Otter is a famously named variety of barley, with a rounded, nutty flavour that works well in just about any kind of ale. It’s a British classic! You might also recognise Golden Promise, which is sweeter and makes a great partner to hop flavours.

There are other varieties of barley that make great beer but aren’t known by name, and these are often blended together as “Best pale ale malt” or simply “Pale ale malt”. You might choose these if the signature flavour of a named variety is too prominent for your particular beer – these blends are designed to have beautifully balanced flavours that work in just about any recipe.

If these blended malts are particularly light in colour, which might be from the harvest or how long the malt is kilned for, these can be sold as “Lager malt” or “Extra pale malt”. You can also find “Low colour” versions of named varieties like Maris Otter, which can be helpful to balance the final colour of your beer.

Munich and Vienna

The modern process for making pale coloured malts was developed in Britain in the 19th Century. Before then, all malts were dried over fires, and were typically much darker in colour and smoky in flavour. The new British process allowed pale golden malts to be produced without strong woodsmoke flavours. Brewers from Germany modified this process to create unique pale malts: the process used in Munich gave a deep, extra-malty flavour, and the Vienna process produced rich, bready flavours and reddish colours. Malts made with the Munich and Vienna processes are now available from maltsters across the world, so when you see a “Munich malt” that means it’s been produced using that process rather than having being grown or malted in Munich.

Mash temperature

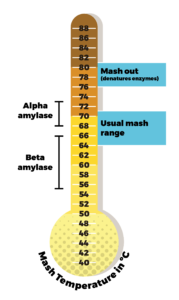

There are two main diastatic enzymes in base malt: alpha and beta amylase. Alpha enzymes are most active at higher temperatures (>68°C) than beta enzymes, which work best at slightly lower temperatures (<65°C). Because the sugars produced by alphas are different than those from betas, adjusting your mash temperature can help you define the body and fullness of your beer.

Beta enzymes produce very fermentable sugars, so mashing cooler can produce drier-tasting beers. Alphas produce more complex (less fermentable) sugars, so mashing at higher temperatures tends to leave more residual sweetness. Many recipes target a balance between the two and aim for around 65-66°C.

Pilsner

The original lagers in Plzeň were made from very pale malt with higher levels of protein than other varieties. Malts with a similar character are now sold as “pilsner malt” or “Pilsen malt” and are typically have a less sweet, almost cracker-like character that works very well in pale lagers.

2-row and 6-row barley

You might see some American recipes specifying “2-row malt”. This refers to the shape of the barley the grain comes from – some varieties have just two rows of ears on each stalk, whereas others are clustered into six rows. US brewers prefer the taste of 2-row, but 6-row has many more enzymes, giving it more diastatic power. It can also be cheaper to grow. Most British and European varieties intended for brewing beer are 2-row, with 6-row barley kept for distilling – e.g. when making whisky – so these names aren’t used as much outside the US.

Come to the dark side, it’s sweet!

Our next chapter takes us to the darker side of malt: caramel, crystal, and roasted malts.

Here you’ll find big flavours, rich colours, and the dark history of stout and porter…