Brew With Us ESSENTIALS – crystal and roasted malts

The crystal (malt) method

Last time we toured the wide world of base malt.

Now it’s time to delve into the dark side: the bold flavours and colours of caramel, crystal, and roasted malts.

As we learned last time, malt is dried and lightly toasted in a kiln as part of the malting process. With base malts, that kilning stage is usually kept at a low temperature to prevent colouring the grain too much. This also preserves the diastatic enzymes – the alphas and betas that break down sugars in the mash.

But what happens if you kiln at higher temperatures? Well, it’s not a million miles off what happens if you cook sugar. You start off with pale and sweet sugar, then as it heats up, it turns more golden. Keep going and it gets darker and develops a deeper flavour. Get the heat right up and the sugar burns, turning black and bitter. The same thing happens with the sugars inside malt as you kiln for longer and at hotter temperatures.

There are two main groups of malts that go through this process, the first being crystal malts. These are kilned directly after germinating, before they are allowed to dry out, which means the sugars inside the grain crystallise with heat. If you break open an uncrushed kernel you should be able to see actual sugar crystals!

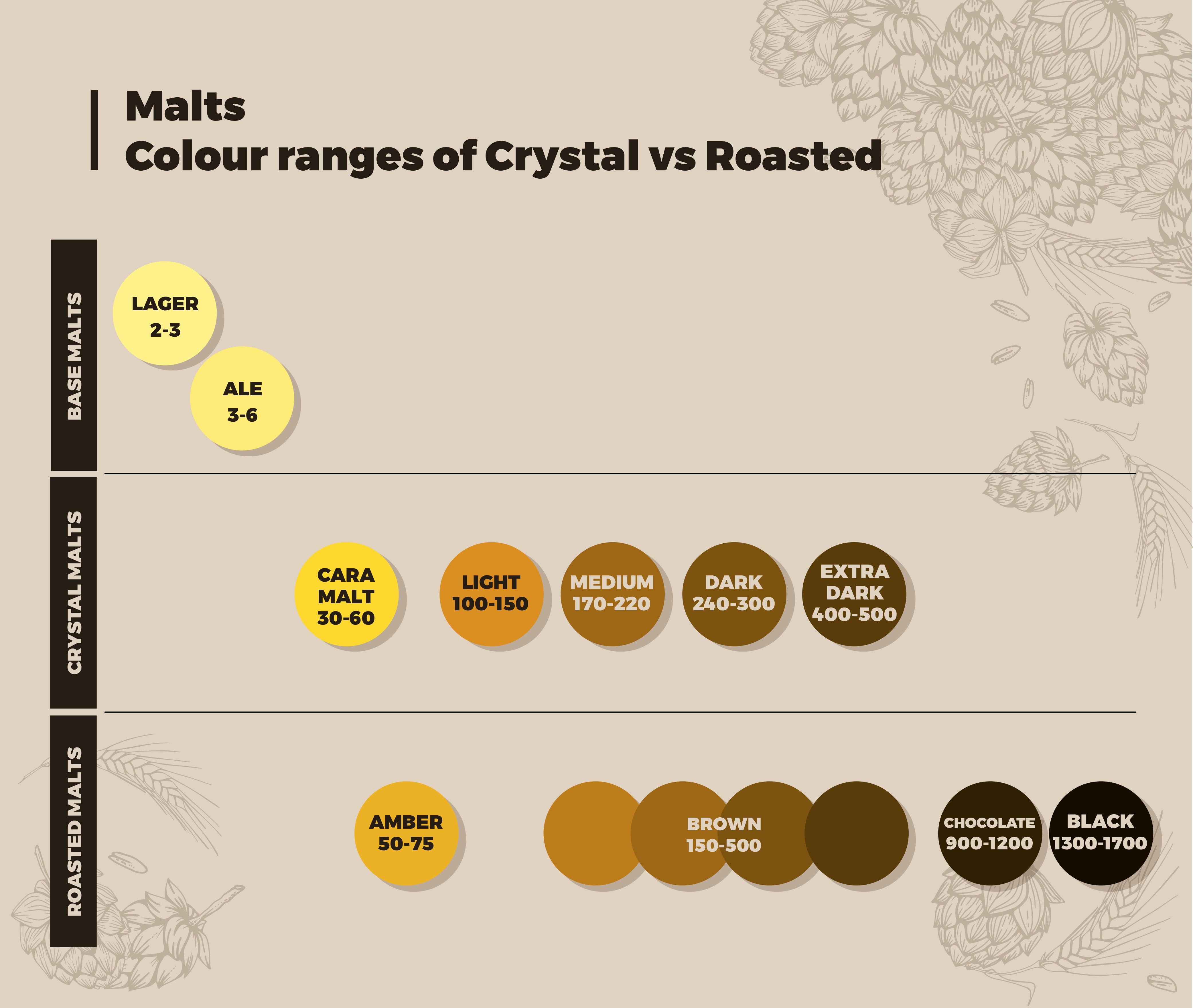

Crystal malts are graded depending on how much they are kilned, from “light” which only gets a little heat, up to “extra dark” which is a deep brown colour. Very light crystal malts are also known as caramel malts – sometimes shortened to “caramalt”.

Because the diastatic enzymes are damaged by the heat in this process, crystal malts need to be used alongside base malts. That’s not a bad thing: the more intense flavours of crystal malts are best used as accents. Lighter crystal malts give a smooth caramel flavour, ascending up through toffee and into dark fruit and molasses with darker malts. A small percentage is best, otherwise these flavours can become cloying.

Roasted malts, our second main group, are dried like a base malt before being kilned at high temperatures. This produces less sweet flavours than crystal malts, ranging from coffee through to bitter treacle. The lightest roast malts are amber malt, followed by brown, and then up to black malt.

A popular roasted malt is chocolate malt, which is darker than brown malt but not as bitter and astringent as black malt. Despite the name, chocolate malt is only the colour of chocolate, and tastes more like black coffee.

Some grains are roasted without malting them first, giving a different flavour. Roasted barley is simply dried and then roasted without germinating it, and gives a mix of the intense, dark bitterness of black malt with the coffee notes of chocolate malt. The most popular stout in the UK (you can guess which) uses a mix of roasted barley and chocolate malt to achieve its dry and dark character.

Say cara, cara

Some maltsters use “cara” to indicate both crystal and roasted malts. Weyermann’s selection ranges from Carapils, an extremely light caramel malt with an EBC colour rating of 4, all the way up to Carafa, a dark roasted malt at 1400 EBC!

The high heat used to make both crystal and roasted malts gives them stronger foam-retaining properties than base malts. Often you may see small amounts of low coloured crystal malt in a recipe to give a more stable head of foam. However, that same high heat changes the mineral composition of the malt, and both crystal and roasted malts contain higher levels of oxygen-sensitive minerals like manganese.

This means that beers with high levels of crystal malt in particular are very sensitive to oxidation, changing that beautiful sweet toffee flavour into something more like wet cardboard (ugh!). The more of these malts you use, the more careful you have to be to reduce unnecessary exposure to oxygen.

As with crystal malts, roasted malts need to be used alongside base malts, typically in small quantities as accents. Because the darkest roasted malts can be quite bitter – like the burnt edges of toast – some brewers only add these malts at the end of the mash, before sparging. This extracts colour from the malt with less of the astringency.

You could also try “cold steeping” dark malts in room temperature water overnight. A bit like making cold brew coffee, this yields a particularly smooth flavour that’s ideal for black IPA, but lacks the roasty “bite” you might want in a stout. Why not experiment to find your preference?

Looking for that special something in your brew?

There’s a malt for that…

Beyond base malts and the sweet darkness of crystal and roasted malts, there are all sorts of unique malts, as well as other grains like wheat and rye, that can give your beer that special something.

Next time we’ll explore these specialty malts and grains!